Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra is a popular devotional text in East Asian Buddhism. It is often referred to as the “Avalokiteśvara Sutra”, or kannongyō (観音経) in Japanese, or more formally the kanzeon bosatsu fumonbongé (観世音普門品偈, “Chapter on the Universal Gate of Kanzeon Bodhisattva”).

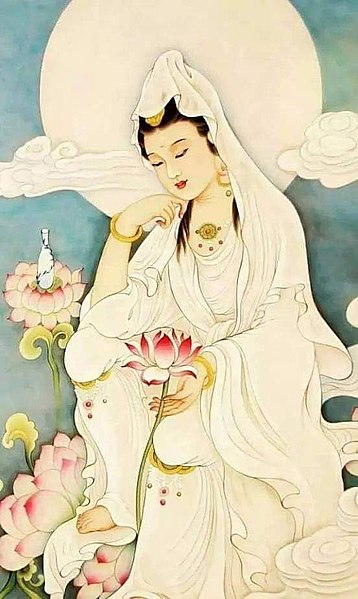

Despite the name, it is not a stand-alone text, but simply a famous chapter in the larger Lotus Sutra. This particular chapter is the main introduction to one of the most popular Bodhisattvas in Buddhism: Avalokitesvara (Kannon in Japanese, Guanyin in Chinese, etc.). The chapter describes the attributes of Kannon that are familiar to Buddhists, such as their vows to help all beings who call on them, their ability to take on various forms to teach people, and their unwavering compassion to lead all beings to Enlightenment.

The chapter as a whole is long and would be difficult to chant, so the verse section, not the narrative section, is frequently used for liturgical purposes. The Lotus Sutra often describes things in narrative form, then summarizes again in verse form. However, even the verse section alone is longer than the Heart Sutra, or the Shiseige, so just chanting the verse section is a bit challenging. In my experience it takes about 5-7 minutes.

For this reason, medieval Buddhists in Japan also devised an even shorter version called the Ten-Verse Kannon Sutra.

The sutra is frequently recited in both Zen and Tendai liturgies, among others, but it is not well known to Westerner lay-Buddhists. I had difficulty finding an online copy I could use as a reference here, even in Japanese, due to its length.

However, ages ago, I picked up a sutra book at the famous Sensōji temple in Tokyo, and once I figured out what the Kannon Sutra was, I copied it character by character to an old version of the blog, but then lost it later when I changed blogs. Recently, I was able to recover the text (not easily) from the original HTML I wrote, and posted it back on here with minor edits.

I have also provided a PDF version here if you want to print it out and use at home.

Also, special thanks to this website for providing much needed reference information on pronunciation and Chinese characters. My original, recovered text had a few errors, embarrassingly.

Examples

I found a few examples on Youtube that you can follow along if you are learning to chant the Kannon Sutra as shown below.

These examples are very similar, other than slight differences in pacing and pronunciation of certain Chinese characters. For people who are learning to recite the sutra, just pick what works until you get the hang of it.

Translation

I decided not to post the translation side-by-side with the text, the way I do with the Heart Sutra and such. This is due to formatting reasons on the blog, plus also length of the text makes this more difficult. I may revise this later.

For now, I highly recommend checking out a modern translation here by the excellent Dr Burton Watson. In that translation, the verse section starts after the phrase “At that time Bodhisattva Inexhaustible Intent posed this question in verse form“. The Buddhist Text Translation Society also has an excellent translation of the verse section here.

Disclaimer and Legal Info

I hereby release this into the public domain. Please use it as you see fit, but if you attribute it to this site, greatly appreciated. Also, please bear in mind this is an amateur work, and should not be taken too seriously.

Dedication

I dedicate this effort to all sentient beings everywhere. May all beings be well, and may they all attain perfect peace.

Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu

The Kannon Sutra, verse section

(2025 edition, with minor typo fixes)

Preamble

| Original Chinese | Japanese Romanization |

|---|---|

| 妙法蓮華經 観世音菩薩 普門品偈 | Myo ho ren ge kyo kan ze on bo satsu fu mon bon ge |

Verse Section

| Original Chinese | Japanese Romanization |

|---|---|

| 世尊妙相具 我今重問彼 佛子何因縁 名為観世音 | Se son myo so gu ga kon ju mon pi bus-shi ga in nen myo i kan ze on |

| 具足妙相尊 偈答無盡意 汝聴観音行 善応諸方所 | gu soku myo so son ge to mu jin ni nyo cho kan on gyo zen no sho ho jo |

| 弘誓深如海 歴劫不思議 侍多千億佛 発大清浄願 | gu zei jin nyo kai ryak-ko fu shi gi ji ta sen noku butsu hotsu dai sho jo gan |

| 我為汝略説 聞名及見身 心念不空過 能滅諸有苦 | ga i nyo ryaku setsu mon myo gyu ken shin shin nen fu ku ka no metsu sho u ku |

| 假使興害意 推落大火坑 念彼観音力 火坑変成池 | ke shi ko gai i sui raku dai ka kyo nen pi kan on riki ka kyo hen jo ji |

| 或漂流巨海 龍魚諸鬼難 念彼観音力 波浪不能没 | waku hyo ru go kai ryu go sho ki nan nen pi kan on riki ha ro fu no motsu |

| 或在須弥峰 為人所推堕 念彼観音力 如日虚空住 | waku zai shu mi bu i nin sho sui da nen pi kan on riki nyo nichi ko ku ju |

| 或被悪人逐 堕落金剛山 念彼観音力 不能損一毛 | waku bi aku nin jiku da raku kon go sen nen pi kan on riki fu no son ichi mo |

| 或値怨賊繞 各執刀加害 念彼観音力 咸即起慈心 | waku ji on zoku nyo kaku shu to ka gai nen pi kan on riki gen soku ki ji shin |

| 或遭王難苦 臨刑欲寿終 念彼観音力 刀尋段段壊 | waku so o nan ku rin gyo yoku ju shu nen pi kan on riki to jin dan dan ne |

| 或囚禁枷鎖 手足被杻械 念彼観音力 釈然得解脱 | waku ju kin ka sa shu soku bi chu gai nen pi kan on riki shaku nen toku ge datsu |

| 呪詛諸毒薬 所欲害身者 念彼観音力 還著於本人 | shu so sho doku yaku sho yoku gai shin ja nen pi kan on riki gen jaku o hon nin |

| 或遇悪羅刹 毒龍諸鬼等 念彼観音力 時悉不敢害 | waku gu aku ra setsu doku ryu sho ki to nen pi kan on riki ji shitsu bu kan gai |

| 若悪獣圍繞 利牙爪可怖 念彼観音力 疾走無邊方 | nyaku aku shu i nyo ri ge so ka fu nen pi kan on riki jis-so mu hen bo |

| 蚖蛇及蝮蠍 気毒煙火燃 念彼観音力 尋聲自回去 | gan ja gyu fuku katsu ke doku en ka nen nen pi kan on riki jin sho ji e ko |

| 雲雷鼓掣電 降雹澍大雨 念彼観音力 応時得消散 | un rai ku sei den go baku ju dai u nen pi kan on riki o ji toku sho san |

| 衆生被困厄 無量苦逼身 観音妙智力 能救世間苦 | shu jo bi kon yaku mu ryo ku hitsu shin kan on myo chi riki no ku se ken ku |

| 具足神通力 廣修智方便 十方諸国土 無刹不現身 | gu soku jin zu riki ko shu chi ho ben jip-po sho koku do mu setsu fu gen shin |

| 種種諸悪趣 地獄鬼畜生 生老病死苦 以漸悉令滅 | shu ju sho aku shu ji goku ki chiku sho sho ro byo shi ku i zen shitsu ryo metsu |

| 真観清浄観 廣大智慧観 悲観及慈観 常願常瞻仰 | shin kan sho jo kan ko dai chi e kan hi kan gyu ji kan jo gan jo sen go |

| 無垢清浄光 慧日破諸闇 能伏災風火 普明照世間 | mu ku sho jo ko e nichi ha sho an no buku sai fu ka fu myo sho se ken |

| 悲體戒雷震 慈意妙大雲 澍甘露法雨 滅除煩悩燄 | hi tai kai rai shin ji i myo dai un ju kan ro ho u metsu jo bon no en |

| 諍訟経官処 怖畏軍陣中 念彼観音力 衆怨悉退散 | jo ju kyo kan jo fu i gun jin chu nen pi kan on riki shu on shitsu tai san |

| 妙音観世音 梵音海潮音 勝彼世間音 是故須常念 | myo on kan ze on bon on kai jo on sho hi se ken on ze ko shu jo nen |

| 念念勿生疑 観世音浄聖 於苦悩死厄 能為作依怙 | nen nen motsu sho gi kan ze on jo sho o ku no shi yaku no i sa e go |

| 具一切功徳 慈眼視衆生 福聚海無量 是故応頂礼 | gu is-sai ku doku ji gen ji shu jo fuku ju kai mu ryo ze ko o cho rai |

Conclusion

| Original Chinese | Romanization |

|---|---|

| 爾時持地菩 薩即從座起 前白佛言世 尊若有衆生 | ni ji ji ji bo sa soku ju za ki zen byaku butsu gon se son nyaku u shu jo |

| 聞是観世音 菩薩品自在 之業普門示 現神通力者 | mon ze kan ze on bo sa bon ji zai shi go fu mon ji gen jin zu riki sha |

| 當知是人功 徳不少佛説 是普門品時 衆中八萬四 | to chi ze nin ku doku fu sho bus-setsu ze fu mon bon ji shu ju hachi man shi |

| 千衆生皆發 無等等阿耨 多羅三藐三 菩提心 | sen shu jo kai hotsu mu to do a noku ta ra san myaku san bo dai shin |

In the coming weeks, I hope to post a couple more such chants from the Lotus Sutra, as they are popular both in Tendai and Nichiren communities in particular, and I am learning to chant these too.

P.S. Featured photo was taken by me at Zojoji temple in Tokyo, Japan, with an image of Kannon Bodhisattva wearing a crown that features an image of Amitabha Buddha.

You must be logged in to post a comment.