My son is in grade school and loves world mythology, especially Greek and Norse mythology (I did too at his age 🥰). But we’ve also been introducing him to Japanese mythology since it’s part of his heritage.

The trouble is is that Japanese mythology feels “scattered” and, due to cultural differences, hard to translate into English without a lot of explanation. Further, some of it just isn’t very kid-friendly.

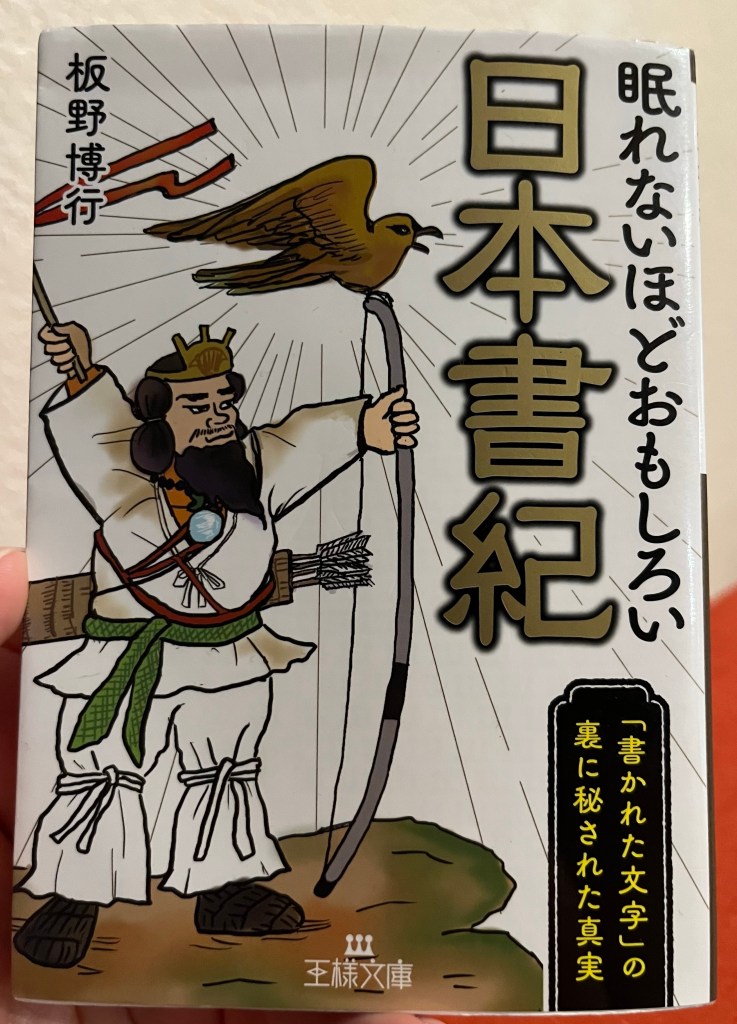

This post is meant to help make sense of Japanese mythology. I learned a lot about it after finding this book in Japanese about the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), a legendary record of Japan’s foundation:

The Nihon Shoki is one of two records composed in the early 8th century about Japan’s history and origins. The other record is the Koijiki (古事記). Both were promulgated by Emperor Tenji, and both cover overlapping yet differing mythologies, so why are there two records?

The book above explains that the intended audiences were different.

The Nihon Shoki is a longer, more polished record of Japan’s foundation intended to impress Imperial China. It seamlessly transitions from mythology to the origins of the Japanese Imperial Family, legitimizing it in the eyes of their rivals in China, and even covers the life of Prince Shotoku. The Kojiki, by contrast, is shorter and includes more salacious details of some myths, and intended for domestic audiences only.

Even between the two records, some myths differ slightly, as we’ll see shortly.

In any case, much of what we know today about Japanese mythology derives from the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki, just as Greek mythology largely derives from only three sources: the Iliad and Odyssey attributed to Homer, and the Theogony by Hesiod.

The Founding Gods

The two gods credited with the founding of Japan are husband and wife Izanagi and Izanami. According to myth, they descended from the heaven realm, called Takama no Hara (高天原) and saw the primordial chaos of the world below. The Kojiki mentions 3 realms, by the way:

- Takama no Hara (高天原) – the heaven realm

- Ashihara no Nakatsukuni (葦原中国) – the earthly realm (e.g. Japan)

- Yomi no Kuni (黄泉国) – the realm of the dead

According to my book above, the Nihon Shoki never mentions the second two, only the heaven realm. Also, if you’ve been playing Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, you might notice some similarities….

Anyhow, Izanagi and Izanami stood over the primordial waters on a heavenly bridge called the Ama no Uki Hashi (天浮橋), dipped a spear or pike (literally hoko 矛 in Japanese, a kind of Chinese spear) into the water, and the salty water dripping from the spear tip encrusted and fell from the tip, forming the first island.

In the Nihon Shoki, they then fell in love with one another and wanted to have kids, but didn’t know how (being very new at this), and got advice from a Wagtail bird (lit. sekirei セキレイ in Japanese). Once they figured out how … the process works, they started giving birth to the “eight islands” of Japan (the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki differ slightly on what these islands are), as well as having many children, including some well-known kami :

- Amaterasu Ōmikami (天照大神) – goddess (kami) of the sun, she was given dominion over the heavens. Her grandson, Ninigi-no-mikoto, is the progenitor of the Imperial family in Japan, according to the Nihon Shoki.

- Susano-o-mikoto (須佐之男命) – god (kami) of storms, he was given dominion over the oceans. His son, Ōkuninushi, is a frequent figure in Japanese mythology especially relating to the founding of Japan.

- Tsukuyomi-no-mikoto (月読命) – god or goddess (kami) of the moon, given dominion over the underworld. Their gender is unclear from the mythology.

However, in the Kojiki version, Izanami died when giving birth to the god of fire, and traveled to the underworld, leading to the myth shown below in the Youtube video.

The Nihon Shoki does not mention this myth, and simply states that they went on to create more gods and goddesses. In this Kojiki version, after Izanagi escaped the underworld, he purified himself under a waterfall, and from the droplets sprang more gods. In the Kojiki version, the three kami listed above were born from the water purifying Izanagi.

Sibling Rivalry

The rivalry between older sister Amaterasu Ōmikami (hereafter “Amaterasu”) and younger brother Susano-o-mikoto (hereafter “Susano-o”) drives a lot of the mythology found in the two records. Amaterasu did not like to lose, and Susano-o had a foul temper, so they often clashed.

In one story, they had a dare to see who had a pure heart (and who didn’t) by giving birth to more gods. In their minds, whoever gave birth to female goddesses had ulterior motives, while whomever gave birth to male gods did not.1 They sealed the agreement by exchanging items: Amaterasu gave her brother her jewels, and Susano-o exchanged his sword. Amaterasu gave birth to three female goddesses, and Susano-o gave birth to five male gods.

The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki differ on what happened next. In the Nihon Shoki, Susano-o cheered at first, but then Amaterasu pointed out that the male gods were born from her jewelry, thus she had the pure heart. In the Kojiki, Susano-o instead points out that the three goddesses were born from his sword, and being such sweet and kind goddesses, he obviously had the pure heart. Thus, depending on the source, different gods declared victory.

Side note: of the five male gods born, one of them, Ame-no-oshihomimi, is the reputed ancestor to the Imperial family. Of the female goddesses, they are still venerated a series of shrines in Fukuoka Prefecture (official homepage here).

In the Nihon Shoki version, Amaterasu won, but Susano-o had a huge tantrum and caused a ruckus, destroying many things, etc. Amaterasu was furious and hid herself in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. This famous myth is often depicted in Japanese artwork. The featured image above (source Wikipedia) depicts the efforts by the other kami to entice Amaterasu to leave her cave and thereby restore light to the world, including a risque dance by kami Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto.

Descent to Earth

Fast-forwarding a bit for brevity, Susano-o, having been previously driven out of the heavens due to his behavior, undertakes some adventures, and rescues a maiden named Kushi-nada-himé from a massive serpent named Yamata-no-Orochi. From the serpents body came the mythical sword Kusanagi, one of the three sacred treasures (神器 jingi) of Japan by the way. The other two, the bronze mirror and jewel, were used in the aforementioned myth to draw Amaterasu out of her cave.

Susano-o and the maiden married, and their son, Ōkuninushi-no-kami (大国主神), who committed many great deeds that helped build and pacify Japan:

Interestingly, Ōkuninushi mostly only appears in the Kojiki.

Later, according to the Nihon Shoki, a kami named Takemikazuchi-no-kami (武甕槌神) was dispatched to inherit the country of Japan from Ōkuninushi who had been entrusted with its care. Interestingly, Takemikazuchi-no-kami is the patron god of the Fujiwara clan (originally the Nakatomi), and guess who helped compile the Nihon Shoki? Fujiwara no Fuhito.

Takemikazuchi demonstrated his power by sitting on a sword, point up, without losing his balance. Yes, that is as painful as that sounds. Needless to say Ōkuninushi was impressed. Ōkuninushi’s son, Takeminakata-no-kami (建御名方神) did not take this well and challenged Takemikazuchi-no-kami to a contest of strength, supposedly the first Sumo match ever, but Ōkuninushi’s son lost and fled elsewhere. Thus, Takemikazuchi-no-kami prevailed and inherited the country.

Later, Amaterasu’s grandson Ninigi2 descended from the heavens to the earthly realm with a retinue touching down at Mount Takachiho on the island of Kyushu.3 There are many versions of this myth. Sometimes Ninigi descends alone, in other versions he descends with various other kami who go on to found their own earthly clans. In some myths, he is obstructed by other kami, and in others he is bearing the aforementioned Three Sacred Treasures. In one myth, upon touching down, Ninigi jams a mythical spear, Ama-no-sakahoko (天の逆鉾) into the peak of the mountain, of which a replica exists today.

In any case, this is where the myths begin to transition to semi-legendary, semi-historical narrative, which is a tale for another day. It’s been fun to read about Japanese mythology in a more cohesive narrative, with humor and historical context thrown in, but I also read Japanese pretty slow, so it may take a little while to get to the next section.

Anyhow, I hope you enjoyed!

P.S. Thank you for your patience as I haven’t had much time to right articles lately. Outside of work and parenting, I have been working a lot on the other blog, plus enjoying Fire Emblem: Three Houses in what little spare time I have. I have more articles queued up and should hopefully get back on a regular cadence soon.

1 I wish I was making this up, but I am not. This kind of ritual to determine one’s heart was called Ukei (誓約) in Japanese, though in modern Japanese 誓約 is read as seiyaku and refers to oaths, vows or pledges in general.

2 More formally known as Amatsu-hikohikoho-no-ninigi-no-mikoto (天津彦彦火瓊瓊杵尊).

3 It’s interesting to note that many of the early myths, and older, more obscure kami in Shinto religion have some connection the island of Kyushu in particular, which is closest to mainland Asia.

Discover more from Gleanings in Buddha-Fields

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.